Shushtar to Chelgerd, Iran

Shushtar to Chelgerd, Iran

If a stranger invited you to his or her house literally seconds after meeting you, would you trust them?

Hospitality is Iran’s trademark. It’d almost be weird *not* to say yes here.

Tom and I took a night bus from Shiraz to Shushtar, which unceremoniously arrived at 3:45 am. Immediately, we were invited to the home of one of our fellow passengers, who let us stay not just until a more palatable morning hour, but for a few days. Nima was a wonderful host, showing us his city, as well as the ups and downs of life in Iran with extreme enthusiasm. Like, extreme.

In the city itself, he took us to see the famed waterworks: a series of canals and dams used to direct water to mills, conceived in the time of Darius I (5th century BC) and including notable expansions built by Romans under the Sassanids (3rd century AD), still working to this day. When busy, he directed us to the overgrown riverside gardens (complete with the remnants of a mansion bombed in the Iran-Iraq war), and implored us to visit the ruins of the Salasel Castle, under which more tunnels related to the water mills could be explored.

He also showed us things we would have never found or dared to try ourselves. After checking out some artisanal crafts in the newly-renovated caravanserai and being serenaded by a woodworker who stirringly sang a few songs for us while also demonstrating his mastery of the setar, we went on a food blitz in the bazaar. Nima seemed to know practically everyone, and took us from stall to stall, where we were given practically unlimited samples of everything. There’s the overwhelmingly sweet: dates dipped in sesame butter, surprisingly stringy halva made from ground sesame. Then there’s the overwhelmingly pungent: all the yogurt and fermented milk items. Those were all fine with me, if… overwhelming. But as grateful as I was to try it, I couldn’t get used to the overwhelmingly sour: all the many pickled vegetables, and even caper berries. Ooof! I felt a little impolite turning down the last few items. At least Tom was able to cover for me, as he genuinely liked all of it.

Most interestingly to us though, Nima provided to us a glimpse of everyday life in Iran, or at least in Khuzestan region. His life seemed a revolving door of friends, with hardly a free moment: even in the evenings when we were about to go to bed, a friend would pop by for tea, maybe a movie or some TV, and chat through the night. And he owns a cool cinema in the middle of town, inherited from his father. Unfortunately, Iranian state regulations are slow to approve movies, and the selection that he does get isn’t really stuff he likes, nor can he play any foreign films. The same goes at home with the TV: practically every Iranian has a satellite dish, which is techically illegal but generally tolerated by the police. In a country where women aren’t allowed to watch live football/soccer matches or sing publicly in front of men, and where people aren’t allowed to dance, satellites are their primary source of “normal” entertainment from the outside world, and that includes bootleg music from Iranian artists operating outside of the country. (“Tehrangeles” is a thing from Iranian-Americans in LA, and there’s also plenty of politically charged music produced in Turkey.)

Heading to the south of town in the evening to see the Sassanid-era Lashgar bridge and the river below, after passing by another few dozen friends of Nima’s and being asked for selfies by Iraqi vacationers at the Abdullah Shrine, we stumbled upon a play happening. Nima, not being religious, didn’t really know what it was other than something to do with Muharram, but anyhow, we were swarmed by costumed actors of all ages wanting selfies, including a man in a niqab…?! Let’s just go with it.

The next day, also joined by fellow traveller Queenie, Nima took us in his car to Choqa Zanbil, a ziggurat dating all the way back to the 1300s BC at the time of the Elamites, built in dedication to various gods and goddesses. Ziggurats are terraced pyramids typically found in Mesopotamia, and Choqa Zanbil lies on the edge (if not outside) of that. It’s absolutely huge, and though likely restored quite a bit, it’s amazing that so much of it is still standing despite being over 3000 years old. Upon close examination, you can see many of the bricks near the gates are covered in cuneiform writing — that’s something restoration can’t do, and those bricks look shockingly new for something this old. This whole complex was lost to the desert sands until its rediscovery in 1961, so the fact that it’s now standing tall amid the landscape is all the more incredible.

We continued onwards to Susa (Shush), where the more probable tomb of the Biblical prophet Daniel lies, brought to the area by a king. (Well, at least there’s no legend here of the growing corpse, like in Uzbekistan…) It’s still curious to me that Daniel is venerated in Islam. While the story of the lion’s den is shared between all three Abrahamic faiths, Daniel isn’t ever mentioned in the Qu’ran or hadiths — some Muslims believe him merely to be a virtuous man rather than a prophet. His tomb here, decorated with mirrors on the inside like most Islamic shrines, is distinct for the curious-looking tower that stands on it, done in Khuzestan’s typical style in 1871. It’s an improvement over the previous arrangement — two adjacent towns quarreling over who got to keep Daniel’s remains (and the lucrative flow of Jewish pilgrims, who also consider him as a virtuous man instead of a prophet) used to dangle them in a coffin over a bridge between them!

After a brief wander around the ruins of the castle of Darius I (there isn’t really much left), we returned to Shushtar to hang out for one last evening before saying goodbye to Nima the next morning. While pretty exhausted from his programme for us, we were very grateful to have had his hospitality, completely unexpected as it was!

Hearing a recommendation from a friend, Tom was determined to head to the Bakhtiari mountain village of Sar Aqa Sayyed, and I decided to go with it as well. With no real info on how to get there, we headed to the town of Chelgerd, well off the beaten track but along a beautiful road through the Zargos mountains and Kuhrang region. People look and dress differently. Upon arrival, an on-the-spot coin flip (figuratively speaking) of a choice led us to a hotel in town, where the receptionist, unable to speak English, called his friend…

Saeed came right to the rescue. An English translation masters student and pretty much the only person in the town of 5000 that could speak English, he set us right up for a trip up to the village the next day — and not only that, he cancelled his plans and took a day off work just to accompany us! Wanting us to make the most of our time in Chelgerd, he called a few friends that evening and they took the two of us around town enthusiastically, visiting the freshwater springs nearby, a waterfall, and a Bakhtiari cemetery. As Saeed explains, lion statues on graves signifies important people like khans.

Bakhtiaris are a nomadic people and an ethnic minority of roughly 3 million in Iran (out of a population of roughly 80 million). Being “formally” converted to Islam by the state, many, including Saeed and his family, generally hold onto their traditions or Zoroastrian beliefs instead. His family stopped being nomadic about 20 years ago, but our visit coincided with the yearly “migration” time: as we had seen on our ride through the mountains, the nomads were leaving the mountains around Chelgerd for the plains around Shushtar, as the season is changing. (At the time of our visit, Chelgerd was just above freezing and Shushtar an incredible 31 degrees Celsius, in the middle of November! Saeed’s father, a retired meteorologist, predicts a warmer winter than usual, chalking it up to climate change and a sadly disconcerting local trend.)

Despite being exhausted, we were pulled along for tea with his family at their house at 11 pm, which we wanted to but could not turn down — that’s Iranian hospitality for you! The next morning, we hired a driver through a friend of Saeed’s friends, and bumped around in the back of a flatbed truck up the winding 35 km gravel road to Sar Aqa Sayyed, passing some beautiful snow-capped mountains… and even a harrowing accident, which the driver emerged from unscathed! Yikes.

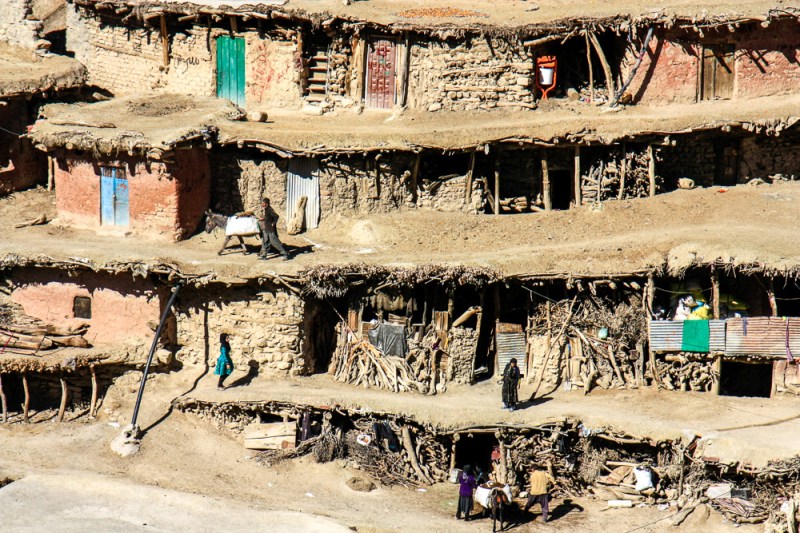

And just like that, around a bend, the village appears and it’s breathtaking. In just a small space, a little over 1000 people live in houses stacked so steeply on the side of a mountain that the roof of one house is the floor of the one above it. Swarmed by kids who just happened to be dismissed from school for the day, we extricated ourselves from their excitement of seeing foreigners and a local friend of Saeed’s took us to a rooftop across from the village for a better view.

Of course, a village like this isn’t without its problems, and that became readily apparent when we began to walk around. For one, given its isolated location and poor roads, it’s pretty much blocked off from the rest of the world in the winter, and the people are quite poor. While there’s electricity, plumbing seems to be an issue, as is garbage: it seems like a very recent initiative has happened with the installation of some very out-of-place and modern-looking garbage cans installed between virtually every other house. Some people are using them. Some… well… I guess to them it’s just a table.

Despite this, the people were all very friendly. This area of Iran only gets a trickle of tourists even in the high season, due to its remoteness, and so having us show up this late in the year probably meant we were going to be the last ones for quite some time. As Saeed translated for us, many families offered to take us in for tea or lunch in their homes simply upon seeing us! We had to turn down most offers due to lack of time, but we did enter one elderly woman’s home for tea and acorns, which Saeed’s friends gleely exploded in the fire used to boil the tea. (It was their first time in Sar Aqa Sayyed too, and a chance for them to see a different type of Bakhtiari life than their sedentary city life.)

In a place where the pace of life is this slow, most people we found just sitting on the roof/floor just chatting or people-watching, and they were happy to see visitors. Others, primarily the women, were gathering firewood, cutting up acorns (used in bread, and also red hair dye for the women), or even weaving the traditional coat that the men wear — or the “piano suit” as I like to call it, since it resembles a keyboard so much. (Saeed explained that in Zoroastrian tradition, the black lines represents the decline of dark forces and the white ones the rising light of human goodness. The extra-baggy parachute pants that go along with the vest? Who knows.) And oddly enough, as we were just about to depart, we witnessed some sort of commotion or argument taking up the attention of the entire village: not a difficult task when people yell from one rooftop to another, and when spectactors can stand on their own rooftops and see the entire village above and below them! We never figured out what went on, but it fizzled out after awhile.

Stopping on the way back to Chelgerd, we had a very late lunch in the form of a makeshift barbecue courtesy of Saeed and friends. I don’t think I’ve ever seen one set up so quickly, or in such a scenic place…

And as luck would have had it, we returned far too late to catch onward transport to Esfahan. Saeed’s solution? “Stay with us for the night. I’ve already told my mom to make dinner. If you refuse we’ll kill you!”

We had a lovely home-cooked dinner of khoresht, doogh, and pomegranates with Saeed’s family, who…basically offered us to stay as long as we wanted. But as kind as they were, we left after breakfast the next morning, but not before playing dress-up to entertain the family…

Heh. Again, Iranian hospitality.

I can relate to your experience in Shushtar so much! More than anywhere else in the country I was whisked off the street into someone’s house, shop or restaurant to chat, feast or sleep. And literally every shop would refuse money from me unless I left it on the counter and exited. It’s such a hospitable town, even by Iranian standards. I also thought the hydraulic system was extremely underrated!