Esfahan, Iran

Esfahan, Iran

After Uzbekistan and Shiraz, I’ve probably seen enough blue-tiled mosques for a lifetime. But even to the jaded eye, Esfahan enthralls.

The most dominant landmark in Esfahan is the Naqsh-e Jahan Square (also Imam Square), the second-largest square in the world after Tiananmen in Beijing. Surrounded by the bazaar and several mosques and palaces, and filled in with fountains, topiaries, and plenty of green space, it’s the centre of activity in the city and full of locals and tourists alike, especially in the late afternoon. It’s great to see such a large public space be used as such: picnickers, bikers, horse carriages, and pedestrians are all active even after dark.

In a bit of an unfortunate trend for both Tom and me that continued throughout the country, it’s also the centre of people trying to practice their English. While Iranians are very friendly and curious, we were pretty socially exhausted after constant interaction in Shushtar and Chelgerd, and didn’t relish a return to incessant requests of selfies or where we were from. (In my case, add a few Chinese racial stereotypes.) Even if they have the best of intentions, the repetition and shallowness wore us down, and so we didn’t spend as much time in the square as I would’ve like, as we became somewhat desperate to be ignored, just for a little while.

To escape it all, we wandered through the endless covered bazaar and headed for the Juma (Friday) Mosque. Built over 900 years ago and added to through the ages (up to at least the 1500s), its four iwans (portals) lead to rooms of vastly different styles, the highlight for me being some very unique brickwork that culminates in the incredible detail of the Taj al-Molk Dome, which has managed to survive pretty much completely unscathed in an earthquake-prone region of the world. (The columns, on the other hand, now visibly lean.) And as usual, the inlaid tile and woodwork are amazing too, so densely packed in such a grand scale, and then I wonder how many years it takes to build something like this!

Back in Imam Square, the Shah Mosque is a complete contrast, far more colourful in nature, beginning with its very blue entrance portal and continuing with its leafy courtyards. Its dome, too, is also the absolute highlight. Not only is it an incredible sight of swirling floral patterns, but it’s an incredible sound to stand directly under it, marked by a stone: making any sort of noise results in a flurry of aurally-satisfying echoes. Scientists have measured 49 with 12 audible to the human ear, though I couldn’t really hear anything beyond 6 — still pretty crazy! This mosque took 25 years to build, after clever shortcuts were devised for the impatient and aging shah who commissioned it. The cost at the time? 25,000 rials. That’s less than $1 nowadays. (I’d love to buy a mosque for that kinda money!)

A stone’s throw away and also in the square is the Lotfallah Mosque, whose façade and interior I found to be my favourite. The smallest of the mosques by far, it’s only got a single room and no courtyard, and yet we spent an hour inside sitting in awe: every inch of the room was covered in Qu’ranic script, florals, or geometric patterns. It’s the first time I’ve begun to understand why the mosques were designed like this: they aim (and of course fall short) to convey the infinite nature of God. And of course, the dome here is again the highlight, with an added twist! Installed at the very center is a peacock-looking thing. With the angle of the window and the natural light coming in, the ray of light serves as its tail. Finding that out left me speechless. Oh, and there’s the fact that this mosque was designed to be exclusively used by the shah’s harem, and there’s a secret tunnel (now closed) from the nearby palace!

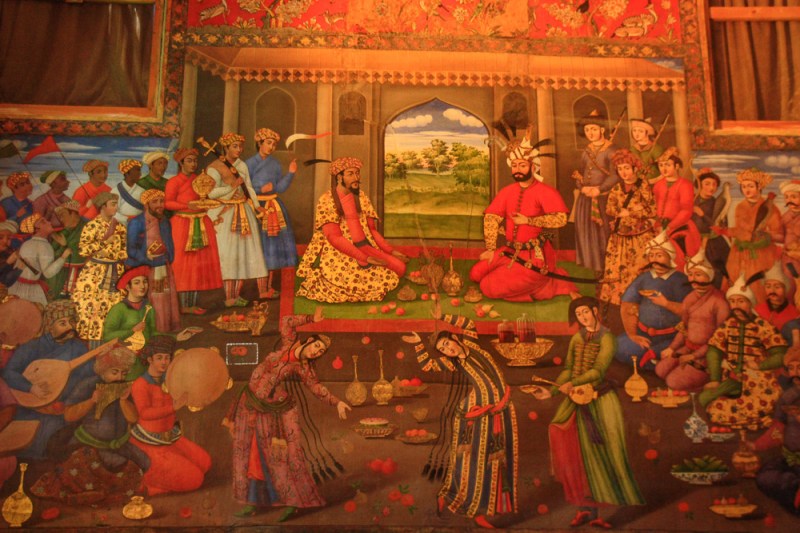

We opted to skip the under-renovation Ali Qapu Palace in the square, and I continued on my own to the Chehel Sotun Palace located a little outside the square, completed in 1649 for another shah. Surrounded by a beautiful and pleasant Persian-style garden and reflected by a long pool, the building (sadly also under a bit of renovation, but still quite nice) has some great work on its wooden ceiling and 40 pillars, leading to an entrance portal full of mirrorwork that pictures simply can’t properly convey. The interior is a completely different sight, covered top to bottom with frescoes of Safavid-era banquets and battles, with plenty of gold leaf too. The Safavids (ruling 15-1700s with Esfahan as their capital; after the Timurids who ruled from modern-day Uzbekistan) being a Persian Shiite empire and all, it’s a little jarring to see such art depicting people who look similar to the ones of today… but minus the modern state-imposed “modesty” and plus a lot more colour and traditional clothing.

Well outside of the square, the city moves like any other big Iranian city. But hidden in the alleys are some historical homes, and we stumbled upon two, now converted for other purposes. One has been turned into a beautiful hotel and restaurant, though lacking customers (despite way more than ample seating) with the cold weather approaching. The other we saw has been turned into a weaving centre: in one architecturally spectacular room are some dioramas. In the other wing, a weaving master and his three accomplices work on one single carpet with probably the most complicated-looking human labour contraption I’ve ever come across. The finished piece will cost something like $500, and just for a few metres!

Walking south, we reached the river, now completely dry (and occasionally on fire…?), spanned by multiple Safavid-era dam-bridges. They seem more like hangout places now, with couples finding an arch to themselves, readers hiding in nooks, and groups of men gathering under the bridge sharing Islamic songs. We… just walked on the dry riverbed, at least when it wasn’t on fire.

Across the river is “New Jolfa”, the Armenian quarter, formed after a shah forcibly moved thousands of people from the Iran-Armenia border town of Jolfa there to use their skills as artists and merchants. It’s now an uber-trendy area, with hardly any sign of Armenia (I saw only one sign), save for a couple of remaining Armenian Christian churches that we were sadly not able to visit. Bustling with well-to-doers at night, we indulged a little at a nice cafe and wandered to grab some fast food… the only non-expensive trendy thing in the neighbourhood.

But we did try some of the local fare too. While khoresht is a lovely warm stew found elsewhere in Iran, khoresht-e mast is a weirder, fluorescent yellow affair, served cold and stringy and comprising of yogurt, eggs, orange peels, and other stuff. Ehhh. Ordering that was perhaps a bit regrettable, but we wandered off a main street one afternoon, finding a crowd gathered and lining up for beryani. It’s got nothing in common with the Indian rice dish of the same name; rather, it’s a delicious pile of ground lamb, sprinkled with cinnamon and walnuts, and served on bread. Mmm! It was a great change of pace from kebabs and rice, variations of which I’ve been eating since entering Kyrgyzstan all those months ago, and the seemingly endless amounts of fast food restaurants.

And despite my general annoyance with the constant racial stereotypes and shallow interactions, the city’s inhabitants (like pretty much every other place in Iran, maybe except Mashhad) are still super friendly, and they certainly mean well. It’s not every place in the world where you can walk down a street and have people yell out “I love you!”, drive past without stopping and yell out “Nice to meet you!” the side of the passenger window, or giggle shyly and try out their best “Hello, how are you, welcome to Iran” in English two steps after they’ve already passed you. These aren’t random one-offs, but regular occurrences — all simply for being a foreigner.

They’ve got plenty amazing things to be proud of, and I’m grateful that they’re happy to share.